IO / NIO

Java IO

An InputStream or Reader is linked to a source of data. An OutputStream or Writer is linked to a destination of data.

Java IO contains many subclasses of the InputStream, OutputStream, Reader and Writer classes. The reason is, that all of these subclasses are addressing various different purposes. That is why there are so many different classes. The purposes addressed are summarized below:

File Access

Network Access

Internal Memory Buffer Access

Inter-Thread Communication (Pipes)

Buffering

Filtering

Parsing

Reading and Writing Text (Readers / Writers)

Reading and Writing Primitive Data (long, int etc.)

Reading and Writing Objects

Java NIO

Java NIO consist of the following core components:

Channels

Buffers

Selectors

Java NIO has more classes and components than these, but the Channel, Buffer and Selector forms the core of the API, in my opinion. The rest of the components, like Pipe and FileLock are merely utility classes to be used in conjunction with the three core components. Therefore, I'll focus on these three components in this NIO overview. The other components are explained in their own texts elsewhere in this tutorial. See the menu at the top corner of this page.

Channels and Buffers

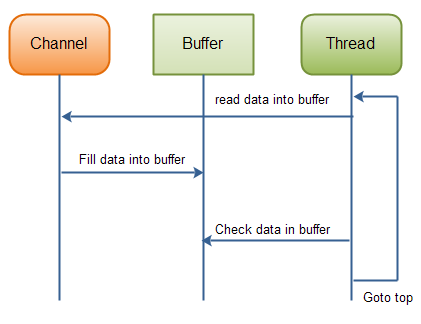

Typically, all IO in NIO starts with a Channel. A Channel is a bit like a stream. From the Channel data can be read into a Buffer. Data can also be written from a Buffer into a Channel. Here is an illustration of that:

There are several Channel and Buffer types. Here is a list of the primary Channel implementations in Java NIO:

FileChannel

DatagramChannel

SocketChannel

ServerSocketChannel

As you can see, these channels cover UDP + TCP network IO, and file IO.

There are a few interesting interfaces accompanying these classes too, but I'll keep them out of this Java NIO overview for simplicity's sake. They'll be explained where relevant, in other texts of this Java NIO tutorial.

Here is a list of the core Buffer implementations in Java NIO:

ByteBuffer

CharBuffer

DoubleBuffer

FloatBuffer

IntBuffer

LongBuffer

ShortBuffer

These Buffer's cover the basic data types that you can send via IO: byte, short, int, long, float, double and characters.

Java NIO also has a MappedByteBuffer which is used in conjunction with memory mapped files. I'll leave this Buffer out of this overview though.

Selectors

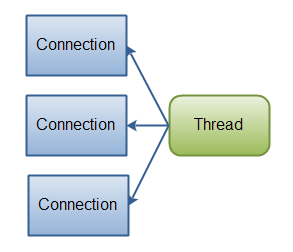

A Selector allows a single thread to handle multiple Channel's. This is handy if your application has many connections (Channels) open, but only has low traffic on each connection. For instance, in a chat server.

Here is an illustration of a thread using a Selector to handle 3 Channel's:

To use a Selector you register the Channel's with it. Then you call it's select() method. This method will block until there is an event ready for one of the registered channels. Once the method returns, the thread can then process these events. Examples of events are incoming connection, data received etc.

Main Differences Betwen Java NIO and IO

The table below summarises the main differences between Java NIO and IO. I will get into more detail about each difference in the sections following the table.

Stream oriented

Buffer oriented

Blocking IO

Non blocking IO

Selectors

Stream Oriented vs. Buffer Oriented

The first big difference between Java NIO and IO is that IO is stream oriented, where NIO is buffer oriented. So, what does that mean?

Java IO being stream oriented means that you read one or more bytes at a time, from a stream. What you do with the read bytes is up to you. They are not cached anywhere. Furthermore, you cannot move forth and back in the data in a stream. If you need to move forth and back in the data read from a stream, you will need to cache it in a buffer first.

Java NIO's buffer oriented approach is slightly different. Data is read into a buffer from which it is later processed. You can move forth and back in the buffer as you need to. This gives you a bit more flexibility during processing. However, you also need to check if the buffer contains all the data you need in order to fully process it. And, you need to make sure that when reading more data into the buffer, you do not overwrite data in the buffer you have not yet processed.

Blocking vs. Non-blocking IO

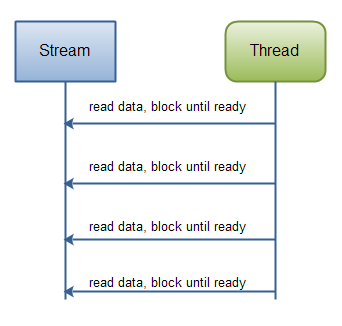

Java IO's various streams are blocking. That means, that when a thread invokes a read() or write(), that thread is blocked until there is some data to read, or the data is fully written. The thread can do nothing else in the meantime.

Java NIO's non-blocking mode enables a thread to request reading data from a channel, and only get what is currently available, or nothing at all, if no data is currently available. Rather than remain blocked until data becomes available for reading, the thread can go on with something else.

The same is true for non-blocking writing. A thread can request that some data be written to a channel, but not wait for it to be fully written. The thread can then go on and do something else in the mean time.

What threads spend their idle time on when not blocked in IO calls, is usually performing IO on other channels in the meantime. That is, a single thread can now manage multiple channels of input and output.

Selectors

Java NIO's selectors allow a single thread to monitor multiple channels of input. You can register multiple channels with a selector, then use a single thread to "select" the channels that have input available for processing, or select the channels that are ready for writing. This selector mechanism makes it easy for a single thread to manage multiple channels.

How NIO and IO Influences Application Design

Whether you choose NIO or IO as your IO toolkit may impact the following aspects of your application design:

The API calls to the NIO or IO classes.

The processing of data.

The number of thread used to process the data.

The API Calls

Of course the API calls when using NIO look different than when using IO. This is no surprise. Rather than just read the data byte for byte from e.g. an InputStream, the data must first be read into a buffer, and then be processed from there.

The Processing of Data

The processing of the data is also affected when using a pure NIO design, vs. an IO design.

In an IO design you read the data byte for byte from an InputStream or a Reader. Imagine you were processing a stream of line based textual data. For instance:

This stream of text lines could be processed like this:

Notice how the processing state is determined by how far the program has executed. In other words, once the first reader.readLine() method returns, you know for sure that a full line of text has been read. The readLine() blocks until a full line is read, that's why. You also know that this line contains the name. Similarly, when the second readLine() call returns, you know that this line contains the age etc.

As you can see, the program progresses only when there is new data to read, and for each step you know what that data is. Once the executing thread have progressed past reading a certain piece of data in the code, the thread is not going backwards in the data (mostly not). This principle is also illustrated in this diagram:

A NIO implementation would look different. Here is a simplified example:

Notice the second line which reads bytes from the channel into the ByteBuffer. When that method call returns you don't know if all the data you need is inside the buffer. All you know is that the buffer contains some bytes. This makes processing somewhat harder.

Imagine if, after the first read(buffer) call, that all what was read into the buffer was half a line. For instance, "Name: An". Can you process that data? Not really. You need to wait until at leas a full line of data has been into the buffer, before it makes sense to process any of the data at all.

So how do you know if the buffer contains enough data for it to make sense to be processed? Well, you don't. The only way to find out, is to look at the data in the buffer. The result is, that you may have to inspect the data in the buffer several times before you know if all the data is inthere. This is both inefficient, and can become messy in terms of program design. For instance:

The bufferFull() method has to keep track of how much data is read into the buffer, and return either true or false, depending on whether the buffer is full. In other words, if the buffer is ready for processing, it is considered full.

The bufferFull() method scans through the buffer, but must leave the buffer in the same state as before the bufferFull() method was called. If not, the next data read into the buffer might not be read in at the correct location. This is not impossible, but it is yet another issue to watch out for.

If the buffer is full, it can be processed. If it is not full, you might be able to partially process whatever data is there, if that makes sense in your particular case. In many cases it doesn't.

The is-data-in-buffer-ready loop is illustrated in this diagram:

Summary

NIO allows you to manage multiple channels (network connections or files) using only a single (or few) threads, but the cost is that parsing the data might be somewhat more complicated than when reading data from a blocking stream.

If you need to manage thousands of open connections simultanously, which each only send a little data, for instance a chat server, implementing the server in NIO is probably an advantage. Similarly, if you need to keep a lot of open connections to other computers, e.g. in a P2P network, using a single thread to manage all of your outbound connections might be an advantage. This one thread, multiple connections design is illustrated in this diagram:

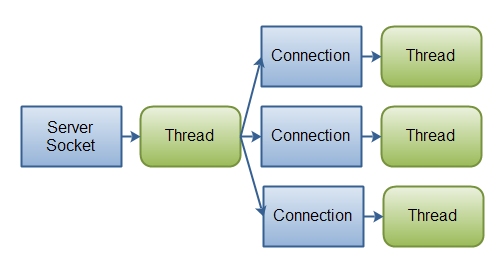

If you have fewer connections with very high bandwidth, sending a lot of data at a time, perhaps a classic IO server implementation might be the best fit. This diagram illustrates a classic IO server design:

Last updated